On Transformers

If there is one thing that is the heart of modern deep learning, it is the transformer. All the incredible advances we see in text, video, images, and sound are all based on the transformer, sometimes with very few changes. The latest language models all still use the original transformer architecture, found in "Attention is All You Need" by Vaswani et al., with very few modifications.[1] It seems unlikely that something will replace the transformer anytime soon, so it is of imminent value to learn the ins and outs of it if you want any understanding of the modern AI landscape.

Before diving into transformers, it is important to establish a foundation. Language models typically process text by tokenizing it. Tokenization involves breaking down a sentence like "I passed the Turing test" into smaller units, or tokens. Depending on the tokenizer[2], this sentence may be split into four or five tokens, with each token potentially containing parts of a word. Each token is then assigned a unique embedding vector, which encodes information such as its meaning, relationships to other words, and more. Tokenization is not just the first step in building these systems—it is arguably one of the most important.

Equally crucial is understanding the attention mechanism, the heart of any transformer. First introduced in a 2014 paper as a solution to machine translation[3], attention helps the model provide the right context for predicting the next word. For example:

"The man ate a lion. After that, he got very tired, went home and _____."

It is clear that the next word here would be "slept." However, from the model's perspective, this is far from obvious without proper context. Without knowing what words came before and their positions, the model has no way to infer what happens next. It might associate "tired" with "sleep" by chance, but it could just as easily generate a host of incorrect guesses. For example, the model might fail to recognize that "he" refers to the man and mistakenly think it refers to the lion. It could also overlook the critical detail that the man just ate a lion and instead assume that, since the man is tired, he went home to eat something. Without context to anchor its predictions, the model can easily misinterpret relationships between words and lose the nuance of the sentence.

This is where attention comes in—it solves these problems in two key ways:

- It is able to understand the position of each word.

- It is able to catch dependencies between each word.

Position is crucial in understanding meaning. In the previous example, without knowing the positions of the words, the model wouldn't be able to distinguish whether the man ate the lion or the lion ate the man—two scenarios with very different implications that could significantly influence what the next word is. Capturing position is relatively straightforward: each word[4] has a unique position, so you can assign it a position vector based on its location in the sequence. However, adding another parameter for position can be computationally expensive. Instead, the position vector is added to the embedding vector, allowing the embedding to represent both the position and meaning of the word. Since the embedding vector is used throughout the model, this effectively incorporates positional information without additional complexity.

Dependencies between words are trickier to capture but still manageable. In the example above, there is a much stronger dependency between "ate" and "lion" than between "ate" and "got." If the model treated every word as equally dependent on every other word, it would miss the nuance of the sentence—and nuance is critical in language. One effective solution is to compute a weighted average of each word's embedding vector. This allows the model to provide the current word with context from previous words, which it can then use to predict what comes next. And indeed, this is exactly what we do.

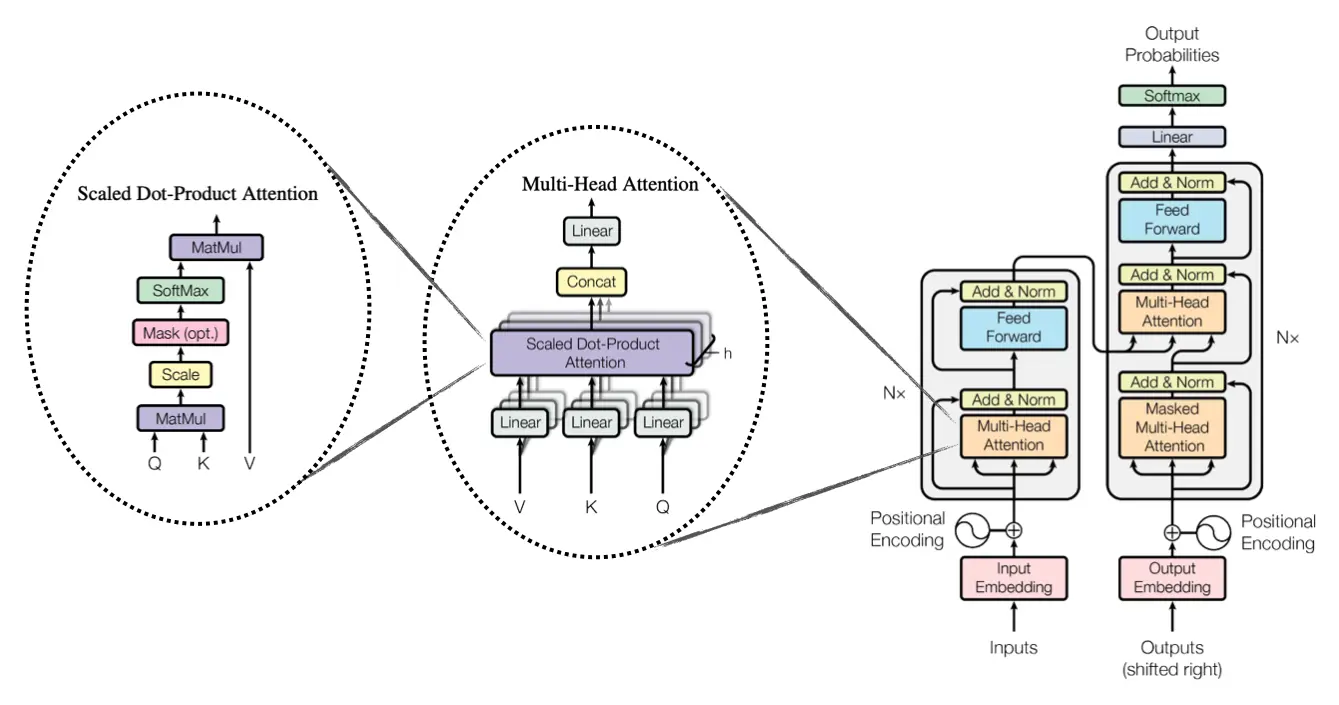

To solve this, we assign each token three vectors: the key vector, the query vector, and the value vector. The key vector represents what the token has to offer to other words, the query vector represents what the token is looking for, and the value vector holds the actual meaning of the word. Each of these vectors has \(n_{\text{embd}}\) elements, corresponding to the embedding dimension. The key vectors are combined into a key matrix of size \((\text{number of tokens}) \times n_{\text{embd}}\), and the same is done for the query and value vectors, resulting in corresponding query and value matrices. It's important to note that these vectors are not random—they are learned during training to capture meaningful relationships between tokens.

Now we have three matrices: \(K\), \(Q\), and \(V\). To determine how much each key vector relates to each query vector, we compute their dot product. A dot product is an effective way to measure similarity between vectors—similar vectors produce a high dot product, while dissimilar ones yield a low dot product. The most efficient way to compute these dot products across all keys and queries is through matrix multiplication, as it performs distributed dot products efficiently.

However, this introduces a dimensional mismatch. We have two options to resolve this: \(K \cdot Q^\top\) or \(Q \cdot K^\top\). Both result in a matrix of the same dimensions, but their interpretations differ.

We want to measure how much each key is relevant to each query, not how much each query is relevant to each key. Remember, the keys represent what is available, and the queries represent what is being sought. In other words, we want to find which keys match the needs of our queries. \(Q \cdot K^\top\) achieves this by letting the queries search for the keys, aligning perfectly with our goal of learning dependencies between words. \(K \cdot Q^\top\), on the other hand, would reverse this logic, making the keys search for the queries, which isn't useful in this context.

Thus, we compute \(Q \cdot K^\top\) to get a new matrix: the weights matrix.

It is helpful to develop some intuition about what the numbers in the weights matrix represent. For example, the value at row three, column four of the weights matrix indicates how much the third token has an "affinity" for the fourth token. In other words, it measures how useful the third token finds the fourth token for understanding the context and predicting what comes next. This value essentially reflects the degree to which the third token considers the fourth token necessary for forming its contextual understanding.

At this point, we apply a mask to the weights matrix, making it lower triangular. This ensures that each token can only "see" tokens that came before it (or itself) and not any tokens from the future. Next, we apply the softmax function to normalize the values, transforming them into probabilities that sum to 1. Finally, we multiply this normalized weights matrix by the values matrix, and voilà—you have a matrix that encodes the context needed to predict the next word!

First, we apply a mask to the matrix, setting the upper triangular part to zero. This ensures that tokens can only "talk" to tokens in their past or themselves, effectively preventing access to future information. This masking is crucial for training the model to operate in an autoregressive manner, as it ensures the model predicts the next word based solely on prior context.

Next, we apply the softmax function to normalize the values, transforming them into probabilities. Without softmax, the raw numbers could be excessively large or small, which would lead to instability in later computations. Softmax resolves this by scaling the numbers smoothly, making them easier to work with.

Finally, we multiply this normalized matrix by the values matrix, resulting in a new matrix that encodes context. At this point, the attention mechanism has successfully captured the relationships and dependencies necessary for prediction.

A few caveats are important to point out: the attention mechanism uses what are called heads. If there is only one head, as in the earlier example, the dimension of the attention head is equal to \(n_{\text{embd}}\). However, if there are \(k\) heads, the dimension of each head becomes \(n_{\text{embd}} / k\). While this reduces the dimensionality of each head, having multiple heads is critical. Multiple heads allow the model to process different features in parallel and focus on various aspects of the input.

For instance, a single high-dimensional head might primarily focus on one feature, such as the beginning of a sentence. In contrast, multiple heads enable the model to attend to a broader range of features across the text, leading to a richer and more comprehensive understanding of the sequence as a whole. This is why modern Transformer systems typically use many heads—GPT-3, for example, employs 128 attention heads per Transformer block.

Before diving into the main Transformer architecture, there are two more key concepts to cover: layer normalization and residual connections. Layer normalization (LayerNorm) is a variation of batch normalization[5] adapted for use in Transformers. It works by computing the mean and variance of each embedding vector and using these to normalize the vector's values.

LayerNorm introduces two learnable parameters, \(\gamma\) (scale) and \(\beta\) (shift), which adjust the normalized values in a linear fashion. These parameters help the model better adapt to the data and maintain flexibility. By normalizing the embeddings in this way, LayerNorm prevents issues like vanishing or exploding gradients, which are common challenges in deep neural networks. Additionally, experiments have shown that LayerNorm not only improves convergence speed but also enables richer representations thanks to the tunable \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\) parameters.[6]

Residual connections are a key advancement that make training deep neural networks more manageable. During backpropagation, one major challenge is the issue of exploding or vanishing gradients. Backpropagation applies the chain rule across each layer of the network, but if any layer produces a very small or very large derivative, the gradient can shrink to near-zero or grow excessively. This prevents weights from updating correctly with respect to the loss function, causing stability and convergence issues. Worse, gradients often vanish completely before they reach the earlier layers, leaving those weights unaffected.

Residual connections address this problem by providing a direct pathway for gradient flow. They work by taking the original input of a layer and adding it directly to the output of the layer's transformation. During backpropagation, when the gradients pass through this addition operation, both terms (the input and the transformation) receive the same gradient. Because the residual connection bypasses intermediate layers, gradients can flow smoothly from later layers back to the input without being diminished or amplified.

This "shortcut" prevents the gradient from getting lost in deep layers, ensuring stable and efficient training. Residual connections are critical in Transformers—without them, convergence would be slow, if not impossible.

Now onto the main transformer itself. Let's go through this step by step:

- First, we take the text and tokenize it.

- Then, we get the embedding vector for each token and store that in a matrix. This matrix is of size \(T \times n_{\text{embd}}\), where \(T\) is the number of tokens and \(n_{\text{embd}}\) is the number of embedding dimensions. Call this matrix \(X\).

- We then add positional embeddings to the embedding vector.

- Now we pass this into the attention mechanism and perform the entire process described earlier. The matrix \(X\) becomes the value matrix.

- Once the weighted averages are computed, we apply layer normalization and add residual connections.[7]

- If it is not a decoder-only model, we go through the entire multi-head attention process again, but this time the queries come from the decoded input while the keys and values come from the encoded input.[8] If it is a decoder-only transformer, this step is skipped.

- Finally, we pass the output through a feedforward network and add residual connections once more.

There are two main types of Transformers: encoder-decoder Transformers and decoder-only Transformers. Decoder-only Transformers are what you get when you remove the cross-attention step (Step 6). This is the architecture used in modern language models, as they are designed for autoregressive tasks with no external input to decode.

Encoder-decoder Transformers, on the other hand, are primarily used for tasks like language translation. While their structure is almost identical to the standard Transformer, there is a key difference: they incorporate an encoder to process the input text and provide context to the decoder. For example, suppose we want to translate the French phrase "Je t'aime les filles belles." Here, the French phrase is the encoded input. The decoded input represents the translation being generated. The word "Je" translates to "I," so "I" would be the first token provided to the decoder.

In this case, it's crucial to have both the encoded text (the full French phrase) and the decoded text (what has been translated so far) when predicting the next word. For instance, to predict the meaning of "t'aime," the decoder benefits from both the encoded context and the token "I." This interaction is achieved using cross-attention, where the decoder leverages information from the encoder to generate the output.

The second multi-head attention layer and the entire encoder stack (often referred to as the "left side" of the Transformer diagram) are unique to encoder-decoder Transformers and are designed for these types of tasks. In contrast, decoder-only Transformers lack these components because there is no encoded input—everything they generate is based solely on the tokens they have produced so far.

This is the transformer block. This can be placed as many times as you want in a neural network. Llama 405b, the biggest open-weights model available, had 128 transformer blocks.[9] The transformer truly is the workhorse of modern AI. It is to AI what CMOS is to the semiconductor industry—imperfect, sure, but it works well enough to produce incredible things.

References:

- "Attention Is All You Need". There are some modifications; see note 7 for details on one. Attention has changed over the years to accommodate longer context windows: Sparse Attention to Create Long Context Windows.

- A good reference for tokens is the Karpathy video. The following Anthropic white paper is also great: Mapping Mind to Language Models.

- Original attention paper.

- It should be "each token," but I am using them interchangeably for clarity.

- Batch Norm Paper.

- Layer Norm Paper.

- In "Attention Is All You Need," residual connections were applied first, then layer norm, then everything else. Modern systems flip this order.

- This flavor of attention, where the keys come from the encoder input and the queries/values come from the decoder input, is known as cross-attention. More on this: Reddit discussion.

- Llama 3 paper.